February is known as National Black History month. The Because of them, we can campaign is a positive campaign that shines the light on people who have paved the way for us. The campaign spotlights everyone from Michael Jackson to Martin Luther King. Check out the site here, to see some of the awesome photos and messages.

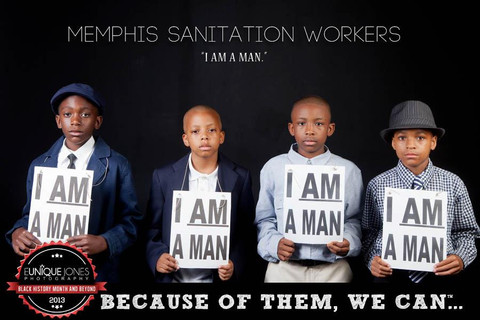

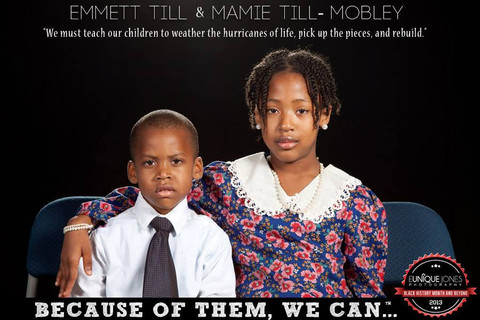

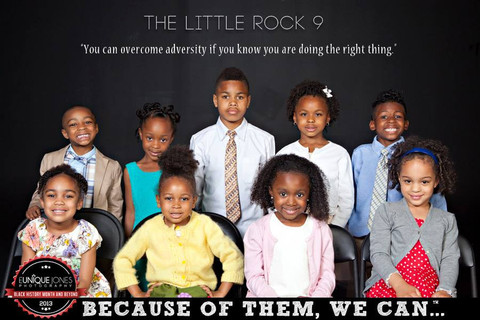

We wanted to showcase the ones that are closest related to Memphis. In the campaign the Memphis Sanitation Workers along with Emmett Till & The Little Rock 9 were highlighted.

The Memphis Sanitation Strike began on February 11, 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee. Citing years of poor treatment, discrimination, dangerous working conditions, and the horrifying recent deaths of Echol Cole and Robert Walker, some 1300 black sanitation workers walked off the job in protest. They also sought to join the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) Local 1733.[1][2]

The Mission of the Campaign is to educate and connect a new generation to heroes who have paved the way. The creator gives us some insight below on what pushed her to start the movement.

The Because of Them, We Can campaign was birthed out of my desire to share our rich history and promising future through images that would refute stereotypes and build the esteem of our children. While I originally intended to publish the campaign photos, via social media, during Black History Month, I quickly realized how necessary it was to go further. With so many achievers to highlight, and thousands of children to engage and inspire, 28 days wasn’t enough. On the last day of February, with just 28 photographs in my collection, I decided to resign from my job in order to continue the campaign. On March 1, 2013, after most national and local conversations about Black History and Achievement ended, I released a photo of a mini-inspired Phyllis Wheatley and began the journey to continue the project for a full year.

A year later I have come to the conclusion that even 365 days aren’t enough. What began as a mother’s passion project quickly evolved into a movement. Today we are committed as ever before to encourage and empower people of all ages and hues to dream out loud and reimagine themselves as greater than they are, simply by connecting the dots between the past, the present and the future.

Emmett Louis Till (July 25, 1941 – August 28, 1955) was an African-American boy who was murdered in Mississippi at the age of 14 after reportedly flirting with a white woman. Till was from Chicago, Illinois, visiting his relatives in Money, Mississippi, in the Mississippi Delta region, when he spoke to 21-year-old Carolyn Bryant, the married proprietor of a small grocery store there. Several nights later, Bryant’s husband Roy and his half-brother J. W. Milam arrived at Till’s great-uncle’s house where they took Till, transported him to a barn, beat him and gouged out one of his eyes, before shooting him through the head and disposing of his body in the Tallahatchie River, weighting it with a 70-pound (32 kg) cotton gin fan tied around his neck with barbed wire. His body was discovered and retrieved from the river three days later.

Little Rock Nine were a group of African American students enrolled in Little Rock Central High School in 1957. Their enrollment was followed by the Little Rock Crisis, in which the students were initially prevented from entering the racially segregated school by Orval Faubus, the Governor of Arkansas. They then attended after the intervention of President Eisenhower.

The U.S. Supreme Court issued its historic Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, 347 U.S. 483, on May 17, 1954. The decision declared all laws establishing segregated schools to be unconstitutional, and it called for the desegregation of all schools throughout the nation.[1] After the decision, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) attempted to register black students in previously all-white schools in cities throughout the South. In Little Rock, the capital city of Arkansas, the Little Rock School Board agreed to comply with the high court’s ruling. Virgil Blossom, the Superintendent of Schools, submitted a plan of gradual integration to the school board on May 24, 1955, which the board unanimously approved. The plan would be implemented during the fall of the 1957 school year, which would begin in September 1957. By 1957, the NAACP had registered nine black students to attend the previously all-white Little Rock Central High, selected on the criteria of excellent grades and attendance.[2] The nicknamed “Little Rock Nine” consisted of Ernest Green (b. 1941), Elizabeth Eckford (b. 1941), Jefferson Thomas (1942–2010), Terrence Roberts (b. 1941), Carlotta Walls LaNier (b. 1942), Minnijean Brown (b. 1941), Gloria Ray Karlmark (b. 1942), Thelma Mothershed (b. 1940), and Melba Pattillo Beals (b. 1941). Ernest Green was the first African American to graduate from Central High School.

Photo Credit: The Because of Them, We Can campaign

Connect With Us:

Facebook: www.facebook.com/xclusivememphis

Twitter: http://twitter.com/xclusivememphis

Instagram: http://instagram.com/xclusivememphis